Designing economic mechanisms: the story of Armando Ortega-Reichert and the Stanford school of economic design

In which we take our first dive into the early history of economic design, starting on the West Coast.

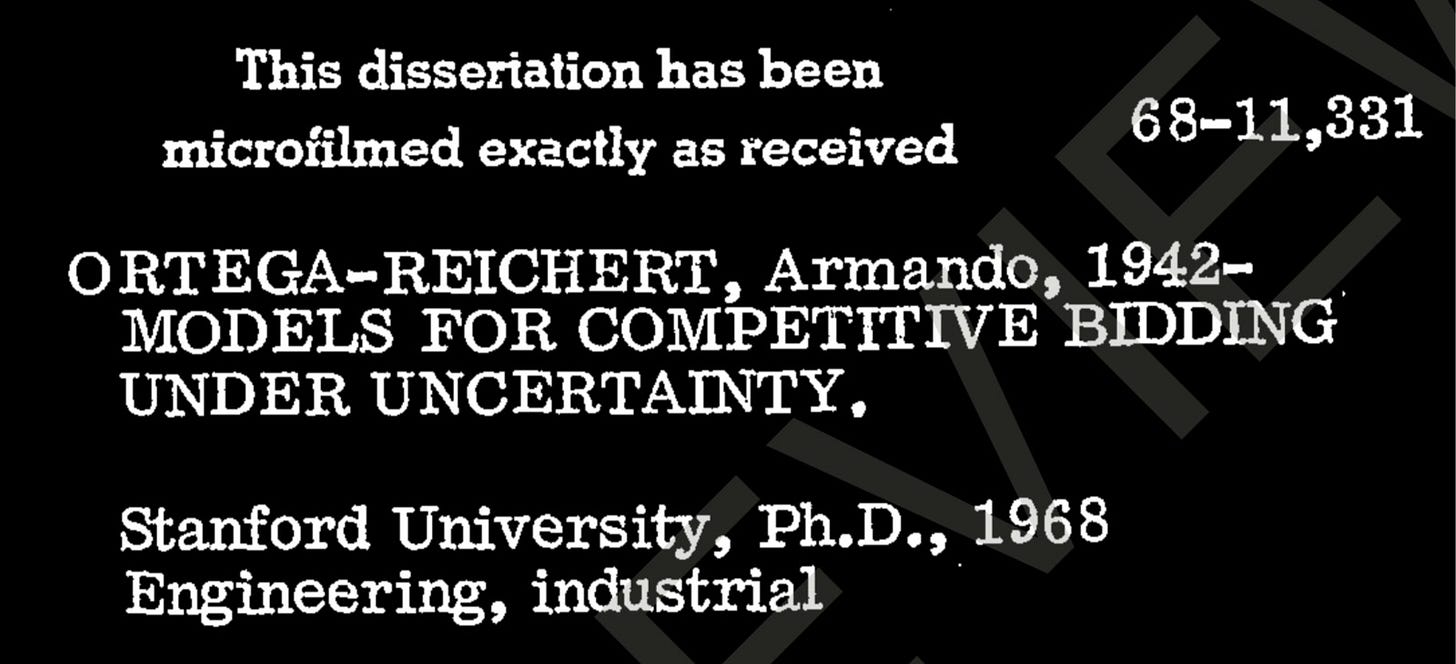

Armando Ortega-Reichert was a graduate student in the industrial engineering program at Stanford in the 1960s. His dissertation, titled “Models for Competitive Bidding under Uncertainty” was submitted in 1968, but never published academically, in his own words because he couldn’t afford the fees.

After graduating, Ortega-Reichert moved back to his native Mexico and started a distinguished career in the civil service. He eventually retired and is now in his eighties. His dissertation might have fallen into complete obscurity if it hadn’t been mentioned by six eventual Nobel laureates in economic sciences: Robert Wilson, Paul Milgrom, Eric Maskin, Roger Myerson, Alvin Roth, and the “godfather of economic auction design” William Vickrey.

All six played major roles in the formulation of economic design fields: Wilson, Milgrom, and Vickrey on auction design, Maskin and Myerson along with Lionel Hurwicz on mechanism design, Al Roth along with Lloyd Shapley (and the late David Gale) on market design.

Ortega-Reichert's dissertation wasn't the first academic work that tried to understand the inner workings of auctions — Vickrey's original paper was published in 1961 — but it was still considered pathbreaking by the small group of peers centered around the operations research group at Stanford's business school and the managerial economics and decision sciences (MEDS) group at Northwestern's Kellogg School.

One major reason was that Armando Ortega-Reichert managed to incorporate the role of information and uncertainty in the unfolding of auctions — his formulation of bids as signaling preceded the Nobel-winning work by Michael Spence on the same topic by a few years. Not even George Akerlof had managed to publish his lemons market paper at that point.

The idea that economic actors are not perfectly informed at lightning speed of everything that happens around them, but that they have to contend with information asymmetries and the competitive advantages or disadvantages they bestow on them, was just beginning to bloom at the time, and Ortega-Reichert was right in the midst of it — except initially, few outside his immediate circle took notice.

This immediate circle included his co-advisor Robert Wilson, who became a doyen to a small group of misfits within the operations research group. Al Roth, himself a student of Wilson’s, remembered that he had “no passion for queuing theory, inventory theory, reliability theory”, and was only saved by Wilson’s interest in “multi-person decision theory”, aka game theory under uncertainty.

Other members of the circle included fellow Nobelists Bengt Holmstrom and Paul Milgrom, all mathematicians or industrial engineers by training rather than economists, all intrigued by the idea that game theory offered a novel angle to think about issues of uncertainty, and most of them eager to dig into auctions as a vehicle to test them out.

Auctions before they were cool

What has since become one of the most lucrative fields of economics was then seen mostly as a backwater in economic thinking which mostly drew scholars from adjacent fields. Auctions were the workhorse of cumbersome government procurement processes, and early papers were published in journals on naval logistics and the construction industry.

So it is no surprise that Ortega-Reichert was not an economist by training, and none of his thesis advisers were.

Fred Hillier, his supervisor, was a professor of operations research at the engineering school. Ron Howard was a pioneering decision scientist at what was then the engineering economic systems department. And Bob Wilson, holder of a DBA from Harvard Business School under game theory pioneer Howard Raiffa, is still at Stanford GSB.

Along with Ken Arrow, another Stanford-affiliated heavyweight and Nobelist who straddled the line between engineering and economics, this circle, somewhat offset from the economics mainstream, pioneered a distinctive engineering approach to economic problems which is now associated with Stanford.

The underlying idea is that we shouldn’t automatically assume that a market exchange bestows efficiency on an economic interaction, but that it decisively depends on how this market was engineered to achieve whatever task it was trusted with.

From that perspective a market isn’t all that different from an internal combustion engine, and an engineering mindset could certainly help with fine-tuning it to tease out that extra quantum of performance by fiddling with the parameters.

That auctions were initially not seen as an object relevant to economic inquiry is an intriguing quirk in the history of economics, but also an important point which reiterates a quandary I pointed out in my newsletter on economic engines and governance mechanisms: It is still not altogether clear where auctions belong in this dichotomy.

Games, auctions, operations research and economics

Simplified, operations research deals with optimization problems under a single principal; the outside world is largely expressed as a source of randomness, a “non-player character”, no matter how well or ill-disposed that outside world is towards the focal principal.1 Game theory deals with the tension between multiple principals, and the Stanford OR group around Bob Wilson was instrumental in expressing that information, or the lack thereof, plays a fundamental role in that tension.

So it makes sense to put auctions within the realm of operations research, with its established connections to engineering and computer science (mostly lacking in economics at the time), and its focus on orchestrating parallel and sequential processes — stocks, flows, transformations — all synchronized to make one principal happy.

But on the other hand auctions inevitably involve counterparties, and it is not obvious from the outset if the auctioneer is intermediating between these counterparties (the famous ”Walrasian auctioneer”) or itself a counterparty. Both cases exist. Once we’re dealing with multiple principals, we’re in the realm of game theory.

To summarize the argument, governance is decision making on behalf of others. A governance mechanism is any economic edifice that takes in multiple, potentially conflicting, interests and spits out an allocation that optimizes collective benefit under some set criterion. (The fundamental typology of governance mechanisms and the selection among them is a central point in EconPatterns, so I will return to this on various occasions.)

An economic engine is an edifice designed purely to further the interests of its proprietor. This includes taking advantage of design flaws of governance mechanisms wherever it detects them. The task of maintaining integrity is then purely on governance mechanisms, and not on economic engines.

Turns out maintaining this separation is tricky not only with auctions, but especially with auction, and at the time of the 2020 Nobel announcement, there was some criticism from those who had followed the explosion of interest in auctions unfold since the early days of FCC spectrum auctions, that while Wilson and Milgrom played an important role in shaping the field, they mostly served as consultants to auction participants rather than making contributions to the design.

I am disinclined to take sides in this discussion, but there is a notable schism in the treatment of auction design in the hugely influential textbooks written by two pioneers in the field, Paul Milgrom and Paul Klemperer.

While Milgrom’s book is mostly dedicated to explaining the formal theory that drives auction design decisions, Klemperer’s is much more circumspect in this regard, also informed by his experiences in the field. The core message is “formal theory is important, but it will only take you so far.”

Needless to say, EconPatterns is staunchly on the side of Paul Klemperer on this.

Just as a quirky side note, in the parlance of decision theory, the source of randomness is often called “act of God” or “act of nature”. The underlying implication is that there is a capricious outside force ready and able to foil our plans, but that that force is not influenced by our actions or does not carefully choose its actions to support or foil our activities. It is just pure dispassionate randomness, which, as we know, does not match the common conception of deities in religion. This has absolutely nothing to do with this discussion on auction design, but I will come back to it in due time.